Indirect mirage

The transformation of IT has been observed for many decades. Applications, architectures and processes are subject to ongoing metamorphosis.

Many things are getting better, but in the area of software licensing, almost all IT manufacturers have failed to do their homework. The singular use of algorithms in a one-to-one relationship - here the PC, there the human - is relatively easy to map and sufficiently well organized via activation servers and the Internet for both providers and users.

Whether it's Microsoft Office 365 or Adobe Suite, the price/performance ratio, activation technique, and license management are logical and largely fair.

Software vendors seem to be completely overwhelmed in complex scenarios when the human-PC relationship is dissolved by a network of on-premise servers, bots, cloud computing, IoT sensors and users.

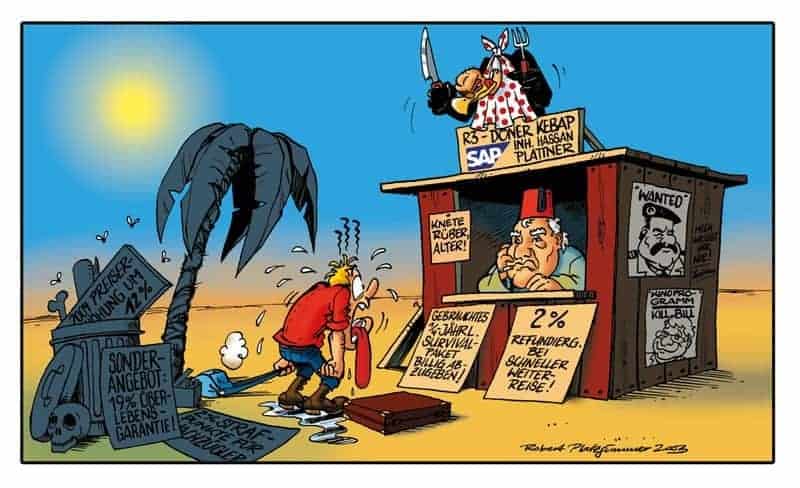

When the data flow becomes multi-dimensional and the data source is not clearly defined, many familiar licensing terms and rules fail. Some manufacturers have chosen the "indirect use" way out. This rule is not only easy to apply, but also flushes a lot of money into the IT vendors' coffers.

The argument is simple: If one program accesses the data resources of another program - i.e. if two programs interact with each other, then the manufacturer of one program says we are being used by the other software, thus licenses must be paid for "indirect use".

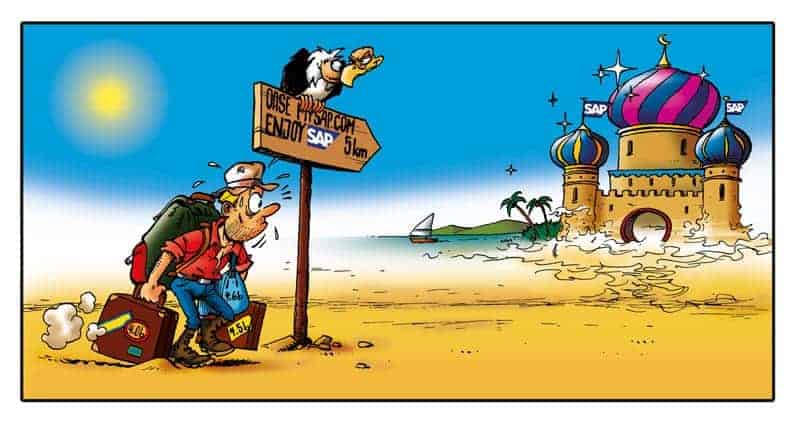

But "indirect use" is a mirage! SAP's desire for even more license revenue is the father of "indirect use". Technically, the interaction of user programs is an interoperability that is precisely regulated in the EU Software Directive.

Accordingly, it is the very function and task of any software to communicate with other programs. If SAP now tries to charge for a fundamental function of algorithms - regardless of how this is argued from a technical, business or organizational point of view - then every IT system leads itself ad absurdum.

"Indirect use" cannot exist. This term is a mirage designed to deceive SAP's existing customers and behind which SAP hopes to generate high license revenues for itself.

With promises and threats, SAP has created a fairy-tale castle that looks equally desirable and threatening from afar. When you get closer, the dream shatters like any other mirage. What remains is a disaster, because in no way can "indirect use" be logically argued.