The Skeletons In The (Supply Chain) Closet

![[shutterstock.com: 109330997, pashabo]](https://e3mag.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/shutterstock_109330997.jpg)

During our presentation of the new SCX Suite last year, the most common question we got from supply chain managers, plant managers and production planners was, “Why do you at GIB think that you can tell us, certified supply chain experts, how we can make our processes better?” GIB’s answer to this question is very simple: We do not offer standard processes; we are just tracking down the skeletons in your closet. And since every improvement process begins with the realization that there is something to improve, GIB’s new indicator model starts right there: with the creation of problem awareness.

GIB supply chain experts wanted to get to the root of the problem rather than treat symptoms. Instead of using SAP big data in the usual way to create new tools, views and analyses, GIB wanted to use the data to highlight gaps, uncover where information is missing, and question processes.

So, how did the experts proceed? What were the main phases that led to the new indicator model? Volker Bloechl, Managing Director of GIB S&D, speaks of five key steps in this context.

Five steps to recovery

Step 1: Formulating an ideal supply chain process. No easy task, considering that there are legitimate company-specific or industry-specific processes. After all, how could one single process be ideal for series and flow production, for discrete manufacturing and the process industry? “The core processes and the core problems are always similar,” explains Volker Bloechl, “Whether teddy bear or aircraft manufacturer – over the years, we have experienced time and again that the problems faced by supply chain experts are very similar at their core.” Problems usually involved imprecise sales planning, inadequate master data, slow-moving items, safety stock, delivery service levels and backlogs—to name a few. “We have chosen a high level of abstraction to achieve comparability and uncover pain points that need to be discussed,” explains the supply chain expert.

Step 2: Defining potential weak points. Once the ideal process had been formulated, the individual process sections were subject to detailed analysis. What happens in the inventory management phase, what activities and planning processes are essential in procurement management, which criteria can be used to evaluate sales planning? GIB’s experts discussed and analyzed these and many other questions. “We had our experienced process and SAP consultants on board,” says Volker Bloechl, who was able to provide numerous topics of discussion thanks to his in-depth practical knowledge as a former operations and scheduling manager. Again and again, the identified parameters were put to the test: Is the activity relevant for all industries? Is the activity meaningful for this specific process section? And last but not least, is it possible to find data in the SAP system that relates to this activity? The experts often had to discard ideas and findings in order to meet their own high standards of simplicity.

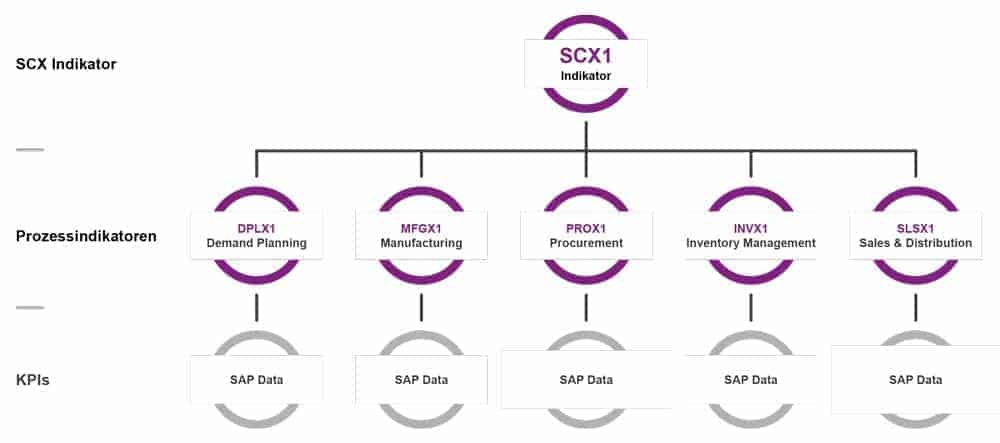

Step 3: Creating key figures. The experts agreed on five process steps, namely Demand Planning, Manufacturing, Procurement, Inventory Management, and Sales and Distribution, and created key performance indicators that make the quality in each step measurable. “This was a major challenge, especially in demand planning,” says Volker Bloechl, because how could the quality of a plan be measured if the original plan was adjusted over time? “With our GIB suite, we have long since solved this problem. We work with versions and save historical data. However, it was important to us that our SCX indicator model could be used independently of our suite. We only access the original SAP data. This is the only way to create a new standard,” he explains. The experts agreed on the evaluation of the materials and articles determined as plannable, their planning horizon, pre-planning without backlogs, and the share of planned materials in the entire material spectrum.

Step 4: Summarizing and prioritizing key figures. The result shows that the GIB experts were successful: Key figures were determined for each process step. But how should these be prioritized? Is the delivery service level more important than the backlog? Is on-time delivery performance more important than quantity reliability? “Everything interconnects,” explains Bloechl, “You don’t have to be a genius to know that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.” For this reason, the experts decided to give each key figure the same priority in the evaluation of the respective process step. "You don't have to be a genius to know that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link." For this reason, the experts decided to give each key figure equal weight in the evaluation of the respective process step.

“We agreed to show the level of quality in percent. An individual evaluation scheme would have required an explanation,” he states. For example, on a six-point scale, the question would have been whether it would have adhered to the school grading system in Germany (with 1 being the best score) or if a higher score would have meant higher quality. Furthermore, the maximum value would always have to be given, whether the scale goes up to ten or up to eighty, etc. “We aim for simplicity in all our products,” says Bloechl, “so it quickly became clear that we needed something that could be understood intuitively and internationally.”

Step 5: Create comparability. A focus point of the indicator model is the comparability of processes in your own supply chain or in comparison to other companies. If the process indicator for manufacturing is at 20 percent and the colleague from inventory management has an indicator of 95 percent, the first did something wrong, and the latter did many things right. Thinking further: If manufacturing in Plant 1 is at 90 percent and in Plant 2 (of the same company) at 50 percent, production planners should urgently discuss why this is the case and what can be done about it.

This comparability also works across companies: two material requirements planners from different companies could certainly have an interesting technical discussion about the respective backlog or delivery service level if their SCX scores differ greatly. “I’m already looking forward to the day when one of our customers greets the other with ‘How high is your SCX score?’,” predicts Bloechl.

Evaluation schemes

What is the point of realizing that your own supply chain is rated at 70 percent? What is the benefit of evaluating the individual supply chain process steps?

First example: A poor evaluation in demand planning shows that many articles and/or materials are not planned at all or, at the very least, are planned inadequately. As a common cause in this case, it is often assumed that the material spectrum is too large, or that planning is not possible. But a look at the forecast often shows that the forecasting procedures are not suitable and that a good planning result can already be achieved with the planning of relevant and plannable articles, or that, quite simply, more information has to flow into the planning system (e.g. from sales and marketing) in order to create a realistic forecast.

Second example: A poor sales and distribution indicator can mean that there is a skew in the delivery service level. If a company always strives to meet the desired delivery date, it may stock up on finished products that are not economically viable. A poor value in the sales and distribution process could also result from a lack of delivery capability despite a full warehouse. The reason for this could be poor sales planning, which leads to producing and storing the wrong products.

“It is important to talk about the figures and their causes,” summarizes Volker Bloechl. “We are happy to aid that discussion. We often hear statements like ‘We’ve always done it this way’ or ‘It doesn’t make sense for us’. During the discussion, it then becomes apparent that time-consuming procedures have crept in unnoticed, or that processes have never been put to the test due to lack of time.” He goes on to say that in his 34-year career with over 200 customer projects, he has never experienced any situation where there was no need for supply chain optimization. “There is always at least one skeleton in the closet,” he jokes. “And I guarantee you, we will find it.”, he quips. "And we ferret them out."